• H O M E • W

R I T E R 'S N I B S • L

I N K S • B

L O G

• C O N T A C T

•

• H O M E • W

R I T E R 'S N I B S • L

I N K S • B

L O G

• C O N T A C T

•

• S

C R I B B L I N G S •

INTERDISCIPLINARY

HUMANITIES

Classroom Comics

GODDESSES

IN WORLD CULTURE

The Maiden with a

Thousand Slippers

PRIMITIVE ARCHER MAGAZINE

Hunting Through

Medieval Literature

INTERDISCIPLINARY

HUMANITIES

Peter

Pan

HORSE

& RIDER MAGAZINE

A Whisper and a Prayer

CONFERENCE

PAPER

Hostages

in the Rose Garden

"If

you steal from one author, it's plagiarism; if you steal from many, it's

research."

Wilson Mizner, 1876-1933, American Author

(Please use appropriate citations)

CHRISTINE

de PIZAN:

An Illuminated Voice

By Doré Ripley, ©2004-23

THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY WRITER, Christine de Pizan, displays an enlightened voice through both text and illustration. Her writings tell the story of a woman very much in touch, although out of sync, with her patriarchal society. By studying her creative output, as well as the process she undergoes to manufacture a finished product, the reader has the opportunity to glimpse the lifestyle of a writer struggling to create and maintain her reputation and standard of living.

After the death of her husband, Christine began writing as a form of therapy: "It is very difficult to keep one's pain bottled up….Fortune could not hurt me so deeply to keep me from having the company of the poets' muses. [T]hey induced me to write tearful complaints in rhyme, to lament my dead beloved husband" (Christine's Vision 192). Chrisine's lyrical rehabilitation led to the invention of a new style of poetry, a genre lamenting widowhood and loss (Blumenfeld-Kosinski 5). Other ways she dealt with her loss and her circumstances was in keeping busy through working and writing. In the decade following her husband's death and before the publication of any of her texts, some believe Christine "worked as a copyist, or perhaps a corrector in a workshop where manuscripts were being prepared for the expanding book trade" (Willard Writings xi). Even though job opportunities for women steadily declined during the fourteenth century (McWebb 8), illumination and transcription were two of the "few professional opportunities open to women" (Willard Writings xi) due to the booming book business (Thomas 11). Drawing and writing were familiar vocations to Christine, and she describes both in her work, The Biography of Charles V, saying the king's outstanding books, were "very well written and richly decorated, for always the best scribes who could be found were engaged to him" (240).

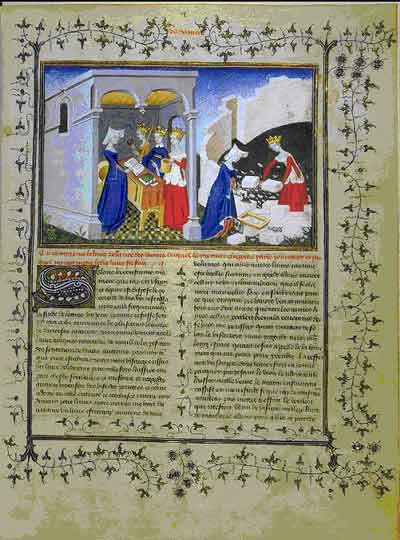

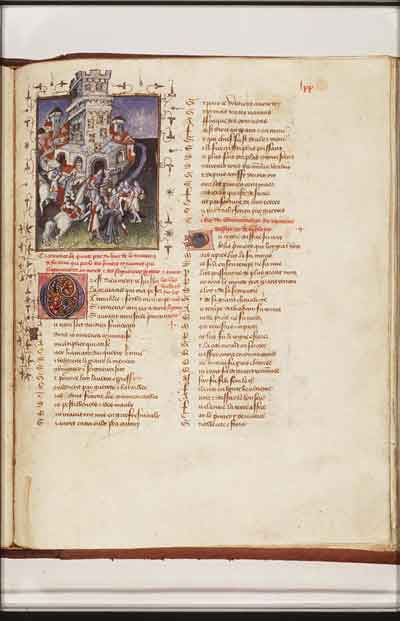

Fig. 1. Cité des Dames Workshop. Reason, Rectitude and Justice appear to Christine; Reason helps Christine build the City. 1407-1408. "Presented to John, Duke of Berry, dated 1407/1408" (Richards xliv). Cité des Dames Workshop, ca. 1405: Housed at Paris, Bibl. Nat., fr. 607 fol. 2" (Meiss Plate 36). Image obtained: Disse, Dorothy. Other Women's Voices. 16 May 2004. <http://www.bnf.fr/loc/bnf030.jpg>

– • –

Unfortunately, Christine never uses the gendered "she" or "her" when speaking of Charles' copyists, and she never claims to have worked for the monarch. In addition, there is no description of how women illuminators or scribes functioned in the male-dominated workshop, but Christine does comment on the notorious reputations of the secular Parisian artists in The Book of the Body Politic, "Among these masters…some who are very skillful…are in Paris, and this is a very fine and remarkable thing…But, to speak briefly of their way of life…(it would please God) that their lives were more temperate and not so lenient as they are now: for the excesses and luxuries in which they habitually indulge in Paris may bring many illnesses and misfortunes upon them" (qtd. in Meiss, Late 14th Century 3). Under these circumstances, it seems doubtful Christine worked within the confines of a Parisian art studio, workshops filled with men of dubious morals.

After Christine de Pizan's rise as a writer she set out to produce her own works, and became "one of the first vernacular authors who supervised the copying and illuminating of her own books" (Richards xxi) (endnote 1). Sandra Hindman in "With Ink and Mortar: Christine de Pizan's Cité des dames (an Art Essay)" studied five copies of the illustration entitled, Reason, Rectitude and Justice appear to Christine; Reason helps Christine build the City, and concludes, "Christine surely supervised the production of these miniatures, instructing her miniaturists either verbally or with written guides that are now lost" (470) (see figs. 1-5, Index of Selected Illustrations)(endnote 2). But how could Christine, a woman concerned about her moral reputation, manage to supervise her works in the male dominated workshops? The answer to that question may never be fully answered.

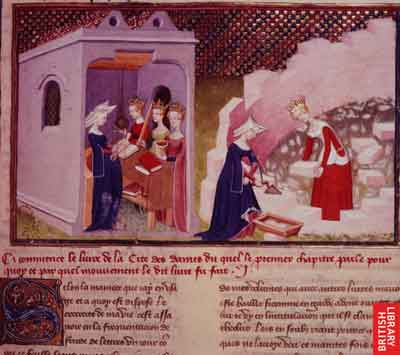

Fig. 2. Cité des Dames Workshop. Reason, Rectitude and Justice appear to de Pizan; Reason helps de Pizan build the City. 1407-1410. "Executed between November 1407 and 1410" (Richards xliv). "Cité des Dames Workshop, ca. 1406: Paris, Bibl. Nat., fr. 1179, fol. 3" (Meiss Plate 35). Image obtained: (Meiss Plate 35).

– • –

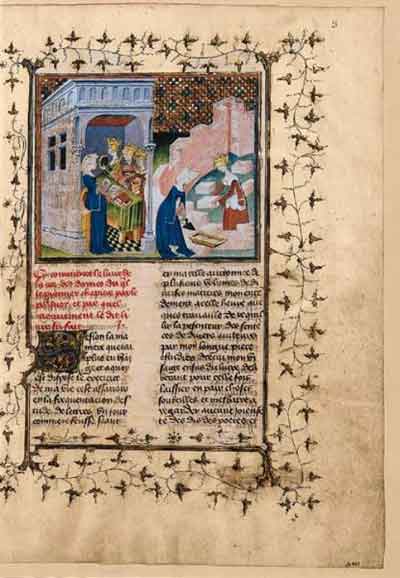

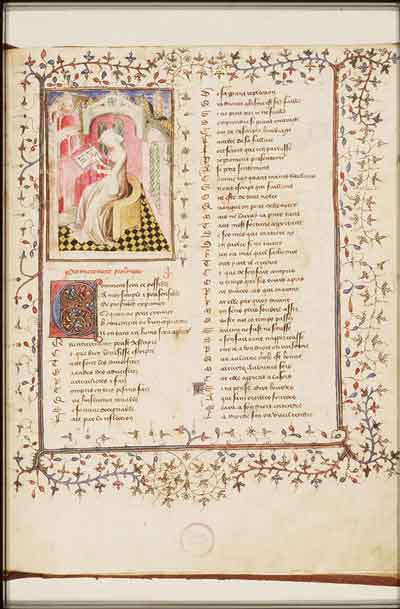

All five diptych-style Reason, Rectitude and Justice illustrations were published in different copies of The Book of the City of Ladies. They represent the moment the Three Virtues appear to Christine in her study and are always pictured on the left, while Christine is always pictured on the right, building the wall of the City of Ladies. Yet, each of the five illustrations are slightly different. The architecture of Christine's study varies; a fluctuating number of books are drawn on de Pizan's desk, and the body postions and clothing of the Three Virtues differs. But Christine's likeness appears consistent throughout: the way she applies mortar while holding up her skirts and the way she holds open the book in front of her. Although agreeing with Hindman's assumption that the works were supervised by Christine because they are similiar, the supposition that Christine left written narrative guides seems unlikely and sketches would not do justice to the colors of the works or forsee the liberties a talented artist might take. In order to get them as consistent as possible, a supervising artist would be needed and who better to supervise her own work then Christine herself.

A thousand words would not be enough to describe how de Pizan should clutch her skirt while cementing building blocks. In addition, one cannot be sure, whether all artists of the period were literate. On the other hand, understanding pictorial direction is easy enough, especially when comparing the early grisaille sketch of Christine presenting her work to the Duke of Orleans, circa 1400 (fig. 6), to the finished illumination, circa 1410-11 (fig. 11). The two artworks depict a kneeling de Pizan, who presents a large metal-clasped book to Louis, Duke of Orleans. In both representations, an elaborately robed Louis sits on a throne, with a fleur-de-lis tapestry hanging in the background, surrounded by three hovering courtiers. Christine's wimple flaunts larger "horns" in the color illumination, but she still wears her familiar "simple" dress (Path of Long Study 69) (see figs. 1-7, 9-12). The multi-colored feathered headdresses of the men in the illumination juxtapose against the rather plain headdresses they sported in the rough grisaille drawing. De Pizan's prior scribal experience would include the skills needed to generate sketches as creative patterns for distribution within the framework of the Bohemian male workshops. Finding de Pizan drawing in the middle of a Parisian workshop seems unlikely, but in light of the claims regarding the presence of female illustrators by both Willard and Millard Meiss (Late 14th Century 3-4), it is apparent, there were at least some female artists who ignored the status quo.

Fig. 3. Cité des Dames Workshop. Reason, Rectitude and Justice appear to Christine; Reason helps Christine build the City. Prior to 1410. "Came from the library of the dukes of Burgundy and was probably copied for John the Fearless and his wife prior to 1410" (Richards xliv). "Cité des Dames Workshop, ca. 1405: Brussels, Bibl. Royale. Ms. 9393, fol. 3" (Meiss Plate 37). Image obtained: (Meiss Plate 37).

– • –

Being a female medieval entrepreneur, Christine's feminine sensibilities would force her to find female artists to facilitate her career as a writer. Christine writes about a woman artist she employed saying, "I know a woman today, named Anastasia, who is so learned and skilled in painting manuscript borders and miniature backgrounds that one cannot find an artisan in all the city of Paris-where the best in the world are found-who can surpass her, nor who can paint flowers and details as delicately as she does, nor whose work is more highly esteemed, no matter how rich or precious the book is. People cannot stop talking about her. And I know this from experience, for she has executed several things for me, which stand out among the ornamental borders of the great masters" (City of Ladies 85).

Since Christine mentions Anastasia in The Book of the City of Ladies completed in 1405, but does not say she was one of the artists employed in illustrating the work, it seems unlikely Anastasia set brush to paper in that book. She must have illuminated some of Christine's earlier texts as evidence of her "experience" with Anastasia. Perhaps Anastasia was the so-called Epître master, the illustrator of both Christine's finest examples of manuscript art, The Letter from Othea, "dated around 1400" (Richards xxiv), and The Book of Fortune's Transformation finished in 1403 (Richards xxiii). The so-named Epître master worked exclusively for Christine from approximately 1403 (Thomas Plate 18) when Christine's works jumped in quality, from the graisaile sketches to illuminated vellum, "augment[ing] the beauty of a manuscript, [and]also dr[iving] up its price" (Buettner, Profane 76) to approximately 1412 (Thoms Plate 18). The exclusive arrangement between Christine and the Epître master indicates a close working relationship, a relationship society would accept between two women, but not between a man and woman.

Fig. 4. Cité des Dames Workshop. Reason, Rectitude and Justice appear to Christine; Reason helps Christine build the City. 1410-1415. "Dated between 1410 and 1415, belonged to Isabella of Bavaria" (Richards xliv). "Cité des Dames Workshop, ca. 1410" (Meiss Plate 38). Image housed and obtained: British Library. "Harley 4431." Images Online. 20 April 2004. <http://ibs001.colo.firstnet.net.uk/britishlibrary/controller/ textsearch?text=Christine&idx=1&start=23>.

– • –

This begs the question, who was the early Epître master? Could it be the Anastasia described in Christine's 1405 work, The Book of the City of Ladies? Even though the dates coincide, it is not possible. Milliard Meiss, the recognized authority of fifteenth-century French manuscript illumination (Endnote 3) asserts Anastasia was not a master, but "skilled in…subordinate specialties rather than in the painting of 'histories' themselves" (Limbourgs 14), which also seems to track with what Christine claims about Anastasia. As to the Epître Master, Marcel Thomas speculates that the artist was not Parisian, and his/her artistic style indicates a possible Lombardy background (Plate 18) similiar to Christine's. Perhaps, the Epître master set up a workshop of artisans that shared a common language, the language of Christine's birth, a workshop employing subordinate specialists, including female border illustrators and background painters. Even while recognizing the differing allegiances of the myriad Italian city-states, Pizzanos and Lombardies did share the same language. A closer examination of two full-page quires from the Epître workshop, dated 1404 (figs. 7-8), may shed light on a single workshop and its many employees.

As previously stated, a master's workshop contained many specialists in addition to master illustrators, including parchment producers, pigment grinders and mixers, border and background painters, scribes and palimpsest creators. The use of so many experts meant different artists worked on the same piece (Thomas 13-14). Masters were paid more than border painters, or pigment mixers, and women were paid less than everyone. Meiss records Albrecht Drurer's amazement at the cheap price he paid for a woman's expertly executed painting (Late 14th Century 3). This cheap source of labor may have trumped gender considerations to the operator of a medieval workshop.

Fig. 5. Anonymous. Reason, Rectitude and Justice appear to Christine; Reason helps Christine build the City. 1410-1418. "Dated between 1410 and 1418" (Richards xliv). Not recorded by Meiss. Image housed and obtained: Bibliothèque Nationale, Fonds francais 1178, f. 3. 20 April 2004. <http://expositions.bnf.fr/utopie/grand/1-56.htm>.

– • –

While charming, close scrutiny of the backgrounds and borders produced in the pre-1405 Epître workshop (figs. 7-8) of Lombardy, do not live up to Christine's enthusiastic description of Anastasia's work. They appear to be executed by the same person, but the borders contain simple designs made up entirely of the three-lobed French leaf. The backgrounds of the 'histories' lack the gold faceted backgrounds produced by the Cité des Dames workshop (see fig. 4). Overall, the backgrounds and borders of the Epître workshop do not display the quality of the later Cité de Dames workshop (figs. 1-4, 9-12). But Meiss believes the Epître master and the Cité des Dame master worked together from 1407 to 1412, and adopted one another's techniques and style (Limbourgs 299). Like the Epître master, the Cité des Dames master exhibits an Italian flair (Thomas 20), so perhaps the two artists associated because of stylistic similiarities and a language connection. If Anastasia worked in the Epître workshop when the Epître master was affiliated with the Cité des Dames master, it would be reasonable to assume she became connected to the later Cité des Dames workshop when the Epître master ceased working altogether. After all, it seems it would be easier for a woman to work in a workshop illustrating a woman's text, perhaps facilitating the connection with Christine. Mutual linguistic and stylistic roots, coupled with ability and economic incentives, may have led these two studios to merge and/or hire female illustrators such as the illustrious Anastasia.

Fig. 6. Anonymous grisaille drawing. Christine de Pizan presenting her book to Louis of Orleans. 1400. " From Epistre d'Othea a Hector." Disse, Dorothy. "Epistre d'Othea a Hector." Other Women's Voices. 4 April 2004. <http://home.infionline.net/~ddisse/index.html> . Path: Christine de Pizan: Epistre d'Othea a Hector.

– • –

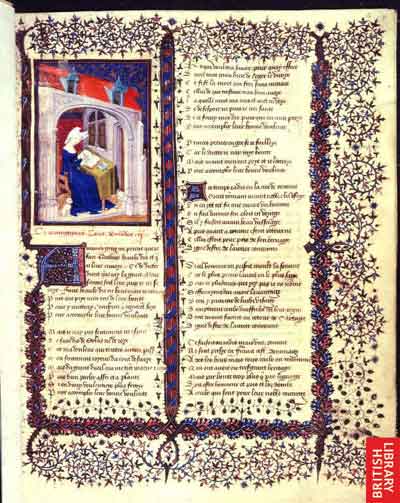

Christine de Pizan admits she wants to be famous and is "a person who desires to be well known" (Fortune's Trans. 91) because books "will for all time to come keep [my] memory alive before princes and the whole world" (Christine's Vision 194). She acknowledges that a good deal of her popularity arose from her gender and records that her audience, "marveled at my labor, not for its greatness but for the novelty to which they were not accustomed" (Debate 44)--"the unusual fact that a woman could write" (Christine's Vision 194). Throughout her works, Christine exploits her feminine novelty by sprinkling in the epithet "I, Christine," while, at the same time, she visually repeats this theme with her many portraits. We see Christine in her study, writing, presenting her work(s) to kings, princes, and clients, and even wielding a trowel in the building of the City of Ladies (see figs. 1-7, 9-12).To maintain her fame and fortune, she presented the famous with her works hoping for a market.

There is no doubt Christine was a prolific author; in her Vision she tells us, "between 1399 when I began writing and the present year, 1405, during which I am still writing, I have compiled fifteen major works, without counting some smaller works, which together are contained in seventy large-size quires" (194). At this juncture in her career, it would seem astonishing to find such a eminent author acting as her own scribe. Sandra Hindman notes that the famous Harley 4431 manuscript of Christine de Pizan's Collected Works, which was originally given to Queen Isabeau of France, was "written entirely in Christine's hand" (461) (figs. 4, 9-12). Fifty-five of Christine's surviving works have been identified as "partial or complete autographs" (Hindman 459). While Christine may have produced many of these herself to maintain her female novelty, it would seem that at some point in her fame, she would need to contract out some of the manual work. A woman author trying to publish (transcribe and illuminate), and distribute her texts would find it difficult to contract with the predominately male workshops, especially in light of their low reputations. However, if Anastasia (or some other female artist) worked in a master's workshop, she would occupy the perfect position to act as a go between for Christine and the masters of those facilities, thereby enabling production of Christine's works and protecting her chaste reputation.

Fig. 7. Master of the Epître d'Othea, Paris. Christine de Pizan writing. 1404. Koinklijke Bibliotheek, National Library of the Netherlands. Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts. 20 April 2004. <http://www.kb.nl/kb/manuscripts/search/index.html>. Path: Author, title=Christine de Pisan; 3. The Hague, KB, 78 D 42.

– • –

Christine was very aware of the adage of her day that women must be and seem virtuous. She warns women, "whether noble, bourgeois, or lower class-be…cautious in defending your honor and chastity against enemies" (City of Ladies 256). A woman's inheritance was especially susceptible and Christine warns widows to beware of those who would "wrong her by claiming what should be hers-as often happens to widows both the exalted and the humble" (Three Virtues 120). Two of a widow's great distresses are "the variety of lawsuits and demands of certain people regarding debts, claims on your property, and income…[and] the evil talk of people who are all too willing to attack you" (Three Virtues 197). When Christine took an assertive stance, arguing in court for her husband's back wages, she was subjected to "many annoying remarks…how many stupid looks, how many jokes from some fat drunkard did I suffer; and because I was afraid of putting my case at risk and was so dependent on its outcome, I hid my thoughts" (Christine's Vision 190). Even so, Christine believed widows should administer their own households, and not "have so little confidence in their own good sense that they will claim that they don't know how to manage their own lives" (Three Virtues 201). Finally, she cautions widows "who are sufficiently comfortable…[that] remarriage is complete folly" (Three Virtues 201). While Christine may have felt comfortable providing for herself, at the same time she knew she must protect her chaste reputation by avoiding direct contact with the dubious men of Parisian workshops. Hand in hand with chastity goes obedience and silence, characteristics she needed to cultivate in order to maintain her elevated status, frequent the noble court, and advance her authorial career by acquiring patrons.

Fig. 8. Master of the Epître d'Othea, Paris. A siege. 1404. Koinklijke Bibliotheek, National Library of the Netherlands. Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts. 20 April 2004. <http://www.kb.nl/kb/manuscripts/search/index.html>. Path: Author, title=Christine de Pisan; 3. The Hague, KB, 78 D 42.

– • –

When it comes to patronage, Christine not only exploits her feminine novelty to advantage, but also flatters and obligates the aristocracy. Many of her works contain presentation pieces (figs. 6, 9, 11-12), showing her gifting her works to a potential patron, a common medieval practice (Buettner, Past Presents 602), though unknown for a woman. She plays on her patron's conceits by illustrating them as benefactors of poets whose worldly courts cannot be surpassed. Christine knew aristocratic tastes and was well acquainted with the royal library, "where [Charles V] had all the most outstanding works compiled by great authors, whether of the Holy Scriptures, or theology, or the sciences, all very well written and richly decorated" (Charles V 240). She comments that the library of Jean, Duke of Berry, contained "a larger number of romances and poetry" (Buettner Profane 75). In medieval Europe, books were considered works of art, an admired luxury, and before mass marketing, their distribution was accomplished via gift exchange (Hindman 459; Buettner, Past Presents 598) and/or purchases and commissions as gifts. In two representative instances, Christine cultivated noble covenants by presenting copies of Fortune's Transformation, produced by the Epître master (Meiss, Limbourgs 9), "to a very important patron, Jean, Duke of Berry" (Koninklijke Bibliotheek 1), and, as a New Year's gift, to the Lord of Burgundy (Christine de Pizan, Charles V 233). Christine's works were coveted by the royal and wealthy as she reminded them of their duties-quite a balancing act.

Fig. 9. Master of the Cité des Dames and workshop, Paris. Christine de Pizan presenting her book to King Charles VI of France. 1410-1411. "From Le Chemin de long estude." Brit. Lib. "Harley 4431." Images Online. 19 April 2004. <http://ibs001.colo.firstnet.net.uk/britishlibrary/controller/textsearch ?text+Christine&idx=1&start=25>.

– • –

Christine was not one to mince words and reminds her noble patrons that if a "simple person should do her service or give her some curious trifle because of affectionate regard, she will consider the person's situation in life as well as the service, value, beauty, or curiosity of the gift, and suitably return the gesture with praiseworthy largess" (Three Virtues 117). Her many strategies seem to have paid off: as she recounts her audience with the Lord of Burgundy. He "told and explained to me how and on what subject it please him that I work….I took my leave, content of my charge, holding this commission" (Charles V 234). At the same time, Christine laments cheap princesses, who should avoid having persons "endure the great trouble and expense in going to the counting house or to her agents one hundred times or more with the same bills before they are paid" (Three Virtues 114). Christine, a woman who longs to live a quiet life in pursuit of study, informs us she "does not care about the lure of money, [and she has] to act against her natural inclination…forced by her great responsibilities to pursue-with great effort-these men of finance and to be led on day after day by their empty promises" (Christine's Vision 197). This could be considered a statement by a woman who must not only be virtuous, but seem virtuous by downplaying the lure of wealth, but she also had to consider the large family she maintained.

Fig. 10. Master of the Cité des Dames and workshop, Paris. Christine de Pizan writing in her study. 1410-1411. "From Cent Ballades." Brit. Lib. "Harley 4431." Images Online. 19 April 2004. <http://ibs001.colo.firstnet.net.uk/britishlibrary/controller/ textsearch?text=Christine&idx=1&start=6>.

– • –

Christine's "great responsibilities" consisted of supporting her mother, out of "love and responsibility, pleasant though it is" (Christine's Vision 197), her children, and a niece. She claims to be poor, saying, I "often shivered under my fur-lined cloak and my fine surcoat that was not often refurbished but kept in good condition" (Christine's Vision 188), hardly a picture of economic disaster. Since her two brothers survived to adulthood, inheriting their father's estates (Willard, Her Life 39), it appears Christine had no real obligation to support her kinswomen. On the other hand, Christine's mother and young niece were likely attracted to the French court, instead of some backwater country estate. The addition of two grown women to Christine's household also had an upside: they could help insure Christine's chastity by acting as chaperone/companions while accompanying her on errands. At the end of The Book of Three Virtues, a veritable do-it-yourself manual for women, Christine boasts she has enough capital, and confidence in her ability, to publish her texts, "I thought I would multiply this work throughout the world in various copies, whatever the cost might be, and present it in particular places to queens, princesses, and noble ladies. Through their efforts, it will be the more honored and praised, as is fitting, and better circulated among other women. I already have started this process; so that this book will be examined, read and published in all countries" (224). In other words, she has enough money, not only to support her family, but also to market her works, in the hope her book (and advice) will trickle down from the nobility to women of many different circumstances to support her circumstances.

Fig. 11. Master of the Cité des Dames and workshop, Paris. Christine de Pizan presenting her book to Louis of Orleans. 1410-1411. "From L'Epître d'Othéa." Brit. Lib. "Harley 4431" Images Online. 19 April 2004. <http://ibs001.colo.first.net.uk/britishlibrary/controller/textsearch? text=Christine&idx=1&start=31>.

– • –

In the spirit of women's intelligence and patronage, Christine presented her Collected Works to Queen Isabeau of France sometime between 1410 and 1415. This collection, now found in the British Library and catalogued as the Harley 4431 manuscript, was executed by the later Cité des Dames workshop (figs. 4, 9-12), and contains none of Christine's political tracts (endnote 4). This beautifully decorated manuscript boasts the only example of a presentation frontispiece consisting solely of females (Buettner, Past Presents 609) (fig. 12), and as previously asserted by Hindman, is completely transcribed by Christine. This document is by far the best-illuminated example of Christine's surviving works; the backgrounds are complicated and exact (figs. 4, 10, upper corners of 11), while the intricate, symmetrical borders contain more than just the three-lobed leaf (figs. 9, esp. 10, 12). Have we finally discovered Anastasia as the creator of the magnificent borders and backgrounds of this manuscript? Christine's final supervision of an illuminated manuscript (Hindman 461) may reflect a female author's words, transcribed by a female scribe, illustrated by a female artist, and presented to a female court. Perhaps this epitomizes Christine's "New Kingdom of Femininity" (City of Ladies 117) as she finally creates her own city of ladies.

Fig. 12. Master of the Cité des Dames and workshop, Paris. Christine de Pizan presenting her book to Isabeau of Bavaria, Queen of France. 1410-1411. "From Epître à la Reine Isabelle." Brit. Lib. "Harley 4431" Images Online. 19 April 2004. <http://ibs001.colo.first.net.uk/britishlibrary/controller/textsearch? text=Christine&idx=1&start=11>

– • –

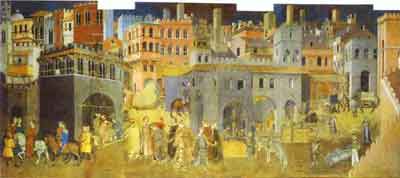

After presenting her Collected Works to Queen Isabeau, Christine no longer supervised the publishing of her manuscripts. She moved from her novel tracts of feminine defense and advice, to tracts on good government, a fashionable genre of art and literature; a genre that includes Suger's A Picture of a Good Feudal King: Louis VI of France, and Lorenzetti's frescos on the Effects of Good and Bad Government (figs. 13, 14). Christine's concern for politics begins quietly in her 1403 work The Path of Long Study, which established her contemporary scholarly reputation (Zago 12). It concludes with allegories on the proper behavior of princes and chivalry (Zago 17), but does not reveal the identities of corrupt aristocrats or knights, which she surely knows but does not wish to offend and risk her lifestyle (at the least). In her letter to Eustache Morel, dated 1404, Christine laments the state of the French state while marketing her texts, "if you would like to see examples of my little understanding in my works, you can order them" (110). Morel's flattering response is guarded; "I am coming to you to learn…you will learn more about my opinions which agree with yours in all things" (112). In 1412, when the French noble factions threaten civil war, Chritine wrote The Lamentation on the Evils That Have Befallen France and finally begins naming aristocratic evildoers. The same year marks Christine's disappearance as an active publisher, and it is likely these two events are connected. It is one thing to write tracts "counteract[ing] the canon of misogynist texts" (McWebb 3, 8), or advising queens and anonymous kings on ethical behavior, but something entirely different to openly scold princely powers about their deeds. Christine was in a precarious position during the lead up to the French civil war; she had patrons on both sides of the fence, and in 1418, in the midst of political upheaval, Christine leaves Paris, never to return.

Fig. 13. Lorenzetti, Ambrogio. Allegory of Good Government: Effects of Good Government in the City. 1338-40. Fresco. Palazzo Publico, Siena Italy. 20 May 2004. <http://www.abcgallery.com/L/lorenzetti/alorenzetti7.html> .

– • –

Christine de Pizan may have been an illustrator alongside the famous Anastasia she describes in The Book of the City of Ladies. As an author, she supervised the production of her works, moving from simple grisaille sketches to illuminations produced by master artists. Her need for a chaste reputation may have led her to interact with women artisans while, at the same time, forcing her to cultivate and maintain her female relatives. Her desire for fame leads her to exploit her feminine novelty both textually and visually, while at the same time, lamenting the treatment of women. Her desire for female community may have been answered in the noble courts and workshops of Paris as Christine's illuminated mind develops through her words and pictures. Nevertheless, in the end, her political opinions forced her to flee her beloved Paris, only to end up weeping in a convent "enclosed here because of…treachery" (Joan 253).

Fig. 14. Lorenzetti, Ambrogio. Allegory of Bad Government: Effects of Bad Government in the City." 1338-40. Fresco. Palazzo Publico, Siena Italy. 20 May 2004. <http://gallery.euroweb.hu/art/1/lorenzet/ambrogio/governme/ 4effect1.jpg> .

– • –

Endnotes

1. Along with Earl Jeffrey Richards, Millard Meiss makes the same assertion; Christine was "the one writer of her time, furthermore, who regularly commissioned illustrated copies of her works" (Limbourgs 8). I add this endnote because neither scholar points to any direct evidence supporting this claim.

2. The dates of individual manuscripts and their illustrations vary by institution and expert. For figs. 1-5, I have provided all available dates in each figure's citation. For purposes of this paper, I have adopted the dates of Earl Jeffrey Richards. "Introduction." The Book of the City of Ladies. New York: Persea Books, 1982. xliv. For purposes of identifying workshops/artists, I have adopted the assignments of Millard Meiss, French Painting in the Time of Jean de Berry. "The Limbourgs and Their Contemporaries. Plate Volume." New York: Braziller, 1974.

3. Even though Meiss' 1974 work appears to be dated, any article concerning the illuminations of Christine de Pizan's many works references Milliard Meiss as the premier expert in this area. These articles include those listed in works cited by Brigitte Buettner, Sandra Hindman, Earl Jeffrey Richards, Marcel Thomas, and Charity Cannon Willard.

4. Works contained within Harley 4431; Cent balades, plusieurs autres balades, encore autres balades, Epistre au dieu d'amours, Debate des ii amans, Live des iii jugemens, Cent balades de dame et d'amant, Dpistre Othéa, Livre du chemin de long estude, Epistles on Roman de la Rose, Livre des trios virtues, and Cité de dames (Hindman 461).

Works Cited

Blumenfeld-Kosinski, Renate. "Introduction(s)" to various writings. The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. Trans. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. Ed. Kevin Brownlee. Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton, 1997. xi-xvi.

British Library. "Illustrated Catalogue." Tours. 19 April 2004 <http://prodigi.bl.uk/illcat/tours/Harl4431.htm>.

---. "Harley 4431." Images Online. 20 April 2004 <http://ibs001.colo.firstnet.net.uk/britishlibrary >.

Buettner, Brigitte. "Past presents: New Year's gifts at the Valois courts, Ca. 1400." The Art Bulletin 83.4 (2001). 598-626.

---. "Profane Illuminations, Secular Illusions: Manuscripts in Late Medieval Courtly Society." The Art Bulletin 74.1 (1992). 75-91.

de Pizan, Christine. "The Biography of Charles V." The Writings of Christine de Pizan. New York: Persea, 1994. 233-48.

---. The Book of the City of Ladies. Trans. Earl Jeffrey Richards. New York: Persea, 1982.

---. "The Book of Fortune's Transformation." The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. Trans. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. Ed. Kevin Brownlee. Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton, 1997. 88-109.

---. "The Book of Three Virtues." A Medieval Woman's Mirror of Honor: The Treasury of the City of Ladies. Trans. Charity Canon Willard. Ed. Madeleine Pelner Cosman. New York: Persea, 1989.

---. "Christine's Vision." The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. Trans. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. Ed. Kevin Brownlee. Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton, 1997. 173-201.

---. "Debate on the Romance of the Rose." The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. Trans. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. Ed. Kevin Brownlee. Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton, 1997. 41-5.

---. "A Letter to Eustache Morel." The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. Trans. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. Ed. Kevin Brownlee. Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton, 1997. 109-12.

---. "The Path of Long Study." The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. Trans. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. Ed. Kevin Brownlee. New York: Norton, 1997. 59-87.

---. "The Tale of Joan of Arc." The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. Trans. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. Ed. Kevin Brownlee. Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton, 1997. 252-62.

Disse, Dorothy. Other Women's Voices. 4 April 2004 <http://home.infionline.net/~ddisse/>. Path: Christine de Pizan; Epistre d'Othea a Hector (illustration).

Hindman, Sandra L. "With Ink and Mortar: Christine de Pizan's Cité des dames (an Art Essay)." Feminist Studies 10.3 (1984): 457-83.

Koinklijke Bibliotheek, National Library of the Netherlands. Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts. 20 April 2004 <http://www.kb.nl/kb/manuscripts/search/index.html> . Path: Author, title=Christine de Pisan; 3. The Hague, KB, 78 D 42.

Lorenzetti,

Ambrogio. "Allegory of Bad Government: Effects of Bad Government in the City."

1338-40. Fresco. Palazzo Publico, Siena Italy. 20 May 2004 <http://gallery.euroweb.hu/art/l/lorenzet/ambrogio/governme/

4effect1.jpg>

.

---. "Allegory of Good Government: Effects of Good Government in the City." 1338-40. Fresco. Palazzo Publico, Siena Italy. 20 May 2004 <http://www.abcgallery.com/L/lorenzetti/alorenzetti7.html>.

McWebb, Christine. "Female City Builders: Hildegard von Bingen's Scivas and Christine de Pizan's Livre de lat cite des dames." The Florin Website. 21 April 2004. 1-11. <http://www.florin.ms/beth5a.html>

Meiss, Millard. "The Late Fourteenth Century and the Patronage of the Duke. Text Volume." French Painting in the Time of Jean de Berry. New York: Phaidon Pub., Inc., 1969.

---. "The Limbourgs and Their Contemporaries. Text Volume." French Painting in the Time of Jean de Berry. With the assistance of Sharon Off Dunlap Smith and Elizabeth Home Beatson. New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1974.

---. "The Limbourgs and Their Contemporaries. Plate Volume." French Painting in the Time of Jean de Berry. With the assistance of Sharon Off Dunlap Smith and Elizabeth Home Beatson. New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1974.

Morel, Eustache. "Morel's Answer." The Selected Writings of Christine de Pizan. Trans. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Kevin Brownlee. Ed. Kevin Brownlee. Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton, 1997. 112-113.

Richards, Early Jeffrey. "Introduction." The Book of the City of Ladies. By Christine de Pizan. Trans. Earl Jeffrey Richards. New York: Persea, 1982. xix-li.

Thomas, Marcel. The Golden Age: Manuscript Painting at the Time of Jean, Duke of Berry. New York: Braziller, 1979.

Willard, Charity Cannon. Christine de Pizan: Her Life and Works. New York: Persea Books, 1984.

---. The Writings of Christine de Pizan. New York: Persea Books, 1994.

Zago, Ester. "Dante Alighieri and Christine de Pizan: Le Livre du Chemin de Long Estude." The Florin Website. 21 April 2004. 12-26. <http://www.florin.ms/beth5a.html>